Many years ago, I ventured into Queens from the suburbs of New Jersey to visit what was then known as P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center. I had heard positive reviews of this museum that is housed in a defunct public school building in what was then the far less developed neighborhood of Long Island City just across the river from Manhattan. Of that day, I recall an immersive experience of lying around in beds and listening to various sound-based works. I was charmed by this art space alive with thoughts and ideas that at that time I had felt starved of in my current work/living situation in New Jersey.

Fast-forward to more than twenty years later and I have been happily settled with my husband and two children in a neighborhood nearby to what is now known as MoMA P.S.1 as well as the not-to-be-overlooked Queens Museum in Flushing Meadow Park. My recent visit to MoMA P.S.1 to see Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991-2011 (Nov. 3, 2019 – Mar. 1, 2020) reminded me of just how fortunate I am to have thought-provoking art in my backyard. This exhibition features first-hand responses as well as those from a distance to the Gulf War in 1991 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. From my perspective of living in the U.S., I remain at a distance from events that feel ever more remote with the passage of time and news cycles switching from one crisis to the next at breakneck speeds. Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991-2011 gives us a moment to pause and to contemplate.

The first half of the exhibition pushes back at propaganda that the Gulf War was a bloodless war completed in 42 days – a myth perpetuated across American media outlets by George H. W. Bush’s administration. There were repeated warnings throughout of this exhibition’s graphic content ranging from large signs around the museum to staff members informing me directly that this show is about war and may not be suitable for my children who accompanied me that day. These warnings were just legal disclaimers ancillary to this show but I felt that their presence throughout were reminders that bloodless war is an oxymoron. Artists in this exhibition have been outspoken in their opposition to MoMA board trustees with direct ties to defense industry companies with direct ties to the wars in Iraq as well as to those connected to the industry of mass incarceration in this country. The action taken by thirty-seven artists in this show of sending an open letter of protest to the museum directors of MoMA and MoMA PS1, #momadivest, further probes institutional complications and forced transparency that created tensions felt in the moment while viewing this exhibition.

The exhibition opens with Kuwaiti artist Monira Al Qadiri’s video Behind the Sun (2013) showing found footage of the Kuwait oil fields set fire to by the Iraqi troops upon retreat in January 1991 and filmed from close range by a local resident. A photograph of an Iraqi soldier burned alive by the US airstrikes is the source for Iraqi artist Dia al-Azzawi’s expressionistic painting Victim’s Portrait (1991). An American photojournalist took the photograph that was reproduced in European newspapers (and shown alongside the painting) but not printed in the American press. The Iraqi artist Shakir Hassan Al Said references the destruction experienced in Iraq in the 1990s through the central void of the canvas in Fragmentation No. 1 (1991). Destruction, decay and death are relayed through these three examples but the many handmade notebooks by numerous artists throughout the galleries stole the show.

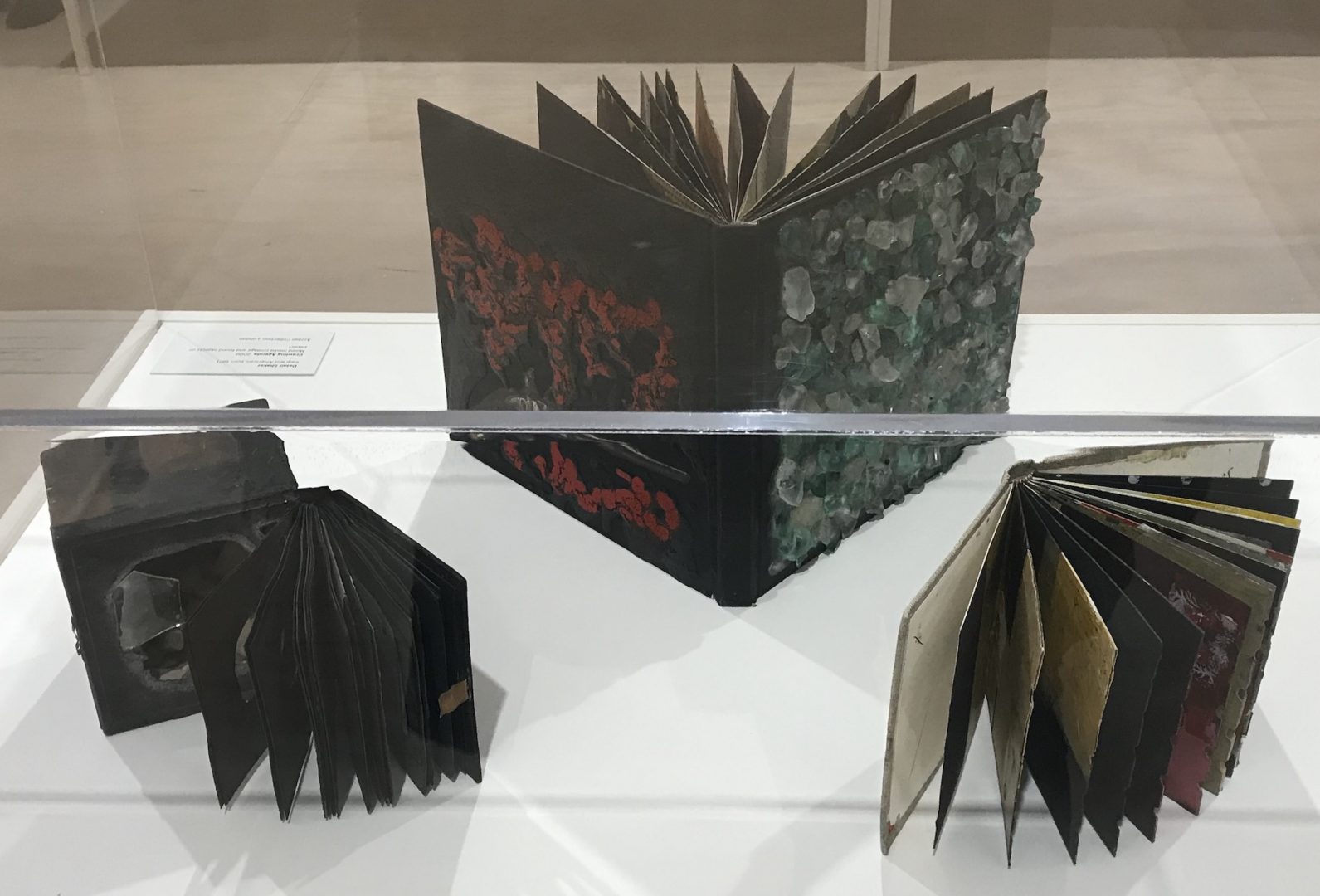

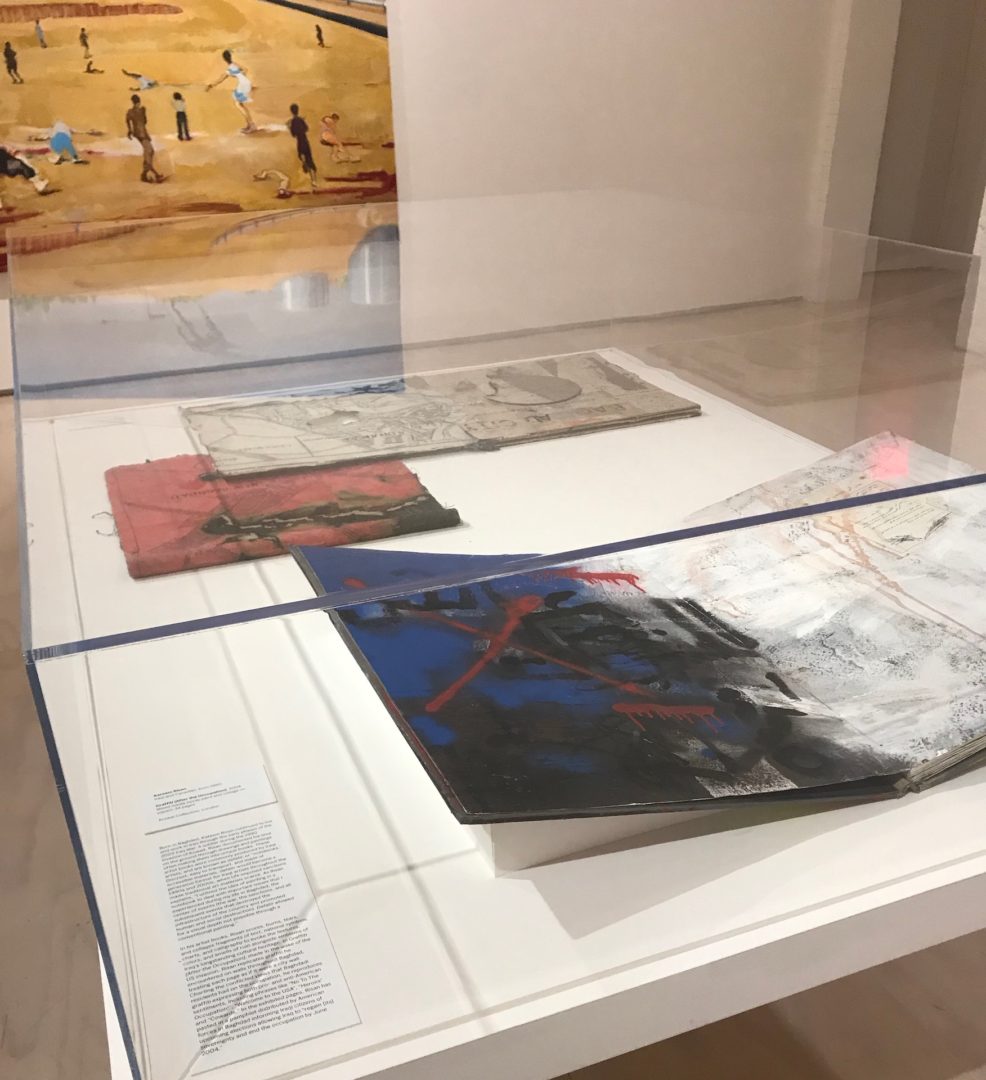

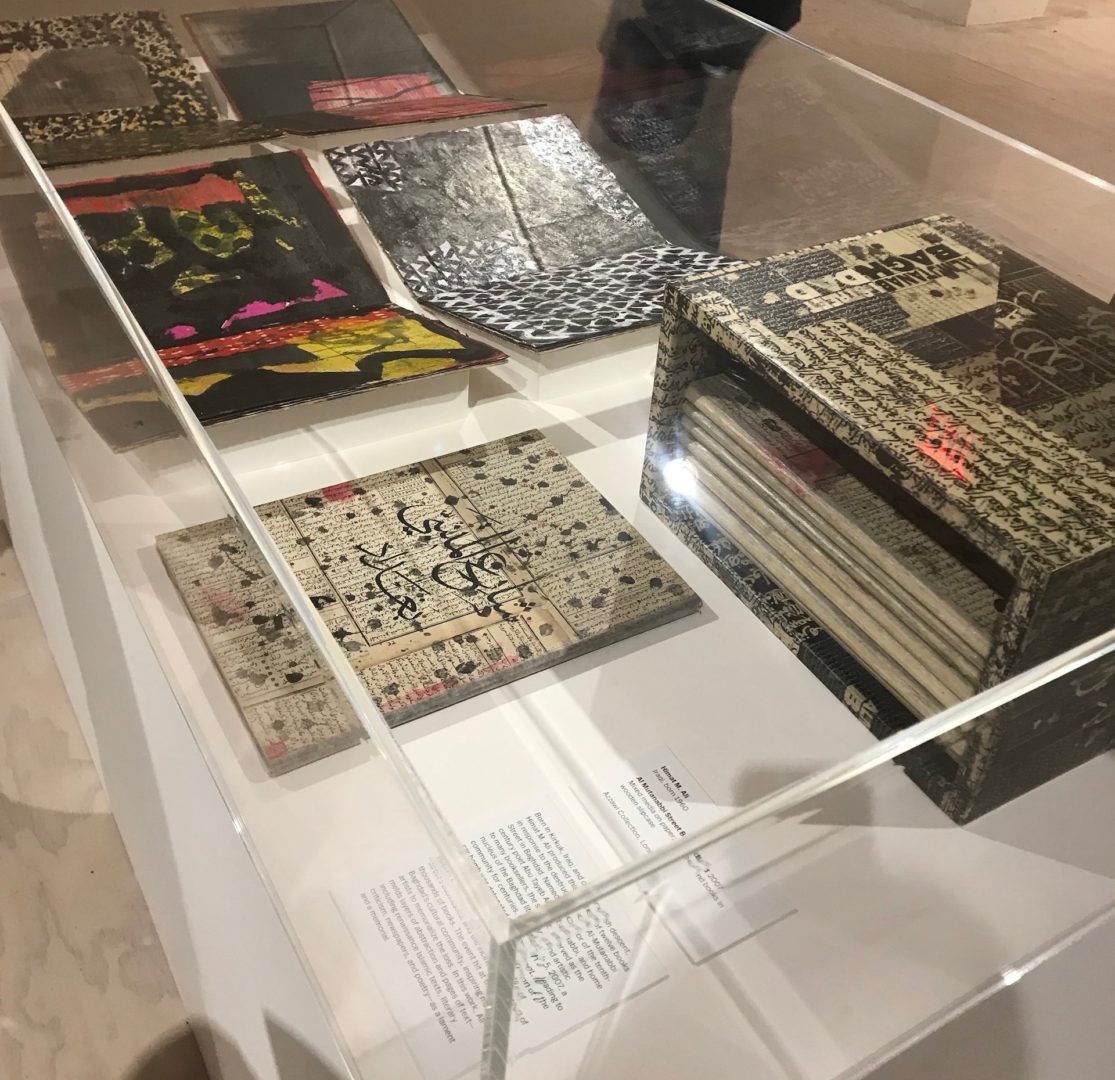

The U.S. sanctions imposed on Iraq throughout the 1990s and 2000s and the U.S. invasion in 2003 limited access to traditional artist materials, which led many of the Iraqi artists in this show to adopt the format of a notebook, known as daftar. This art form was pioneered and championed by the artist Dia al-Azzawi, a prominent figure among this group and whose career spans many decades. Azzawi contributed numerous works to this show, among them the 28-page notebook War Diary, No. 1 (1991), made while watching the bombing of Iraq on television and from London. In addition to his own work, Azzawi loaned from his private collection a good portion of the notebooks by other artists in this exhibition including those by Shakir Hassan Al Said (Iraqi), Ghassan Ghaib (Iraqi and American), Hanaa Malallah (Iraqi and British), Nazar Yahya (Iraqi), Delair Shaker (Iraqi and American), Rafa Nasiri (Iraqi), Mohammed Muhraddin (Iraqi), Ghaith Abdulahad (Iraqi), Kareem Risan (Iraqi and Canadian), and Mahmoud Obaidi (Iraqi and Canadian). This exhibition is quietly yet firmly dominated by the dafatir (notebooks) by artists spanning multiple generations. This was a welcomed surprise and introduction to artists whose work I was unfamiliar with until now.

The mixed media notebooks in this show draw upon abstraction, graffiti, destruction, decay, calligraphy, diaries and more. One can draw connections to traditional Islamic art practices of text and image using the format of a book as well as to a history of literature deeply embedded within Iraq’s cultural heritage. The material destruction of this history as a result of conflict is addressed in Wafaa Bilal’s (American, born Iraq, left as refugee during Gulf War), installation of bookshelves filled with books of blank pages representing the loss of 70,000 books from the libraries of the College of Fine Arts at the University of Baghdad due to the looting that took place during the U.S. invasion. There is an interactive element to this piece inviting visitors to purchase a book from the museum shop and then add that book to the bookshelves in the galleries to replace a blank book. The books purchased by visitors are then donated back to the looted library.

Dia al-Azzawi’s monumental painting, Mission of Destruction, is a direct response to the impact of the 2003 U.S. occupation of Iraq, events that contributed to the instability that has sparked recent protests in Iraq. As I stood before this piece, I kept thinking about the current proliferation of murals in Baghdad, specifically along an underpass of Baghdad’s creative hub, Tahrir Square, and the remaining walls of the bombed-out 15-story concrete shell of a building known as the Turkish Restaurant. This building’s derelict condition is also due to the 2003 U.S. invasion but has very recently been taken over by protesters frustrated with the current Iraqi government. The protesters have covered the walls with commemorative portraits to individuals who were killed in the protests among other symbolic imagery to represent their cause. After viewing photographs of these murals posted online by various news outlets, I was struck by the sense of urgency in these bold and monumental expressions, all created in a public space and intended for mass consumption. The large scale and fixed locations of these murals contrast the portability and intimacy of the many notebooks in the MoMA PS1 exhibition but both the recent murals in Baghdad and the notebooks throughout this exhibition are both founded upon the ruins of war.

Hiwa K (Iraqi and Kurdish), used remnants of destruction that litter the battlefields in Iraq for The Bell Project (Iraq) & (Italy) 2007-2015. In the museum, visitors walked around a bell that was cast from the metal debris of weapons used in combat zones and collected by a Kurdish ironmaster. Normally these pieces of metal would have been melted down into bricks and re-sold by the ironmaster but in collaboration with the artist Hiwa K, he cast the metal into a bell that was to be installed in a church in Italy. The final product, too large to install in the Italian church’s niche, has taken objects of war and destruction and transformed them into an object that I associate with peaceful gatherings, quiet contemplation and the passage of time. The artist presented a reversal of a process that happened during WWI in Europe when bells were melted down to make weapons as well as points out that the found metal pieces in Iraq originated from weapons used by foreign forces or from weapons sold to Iraqi forces by rich nations. These pieces of metal debris were then gathered, melted and returned to the West in a peaceful form.

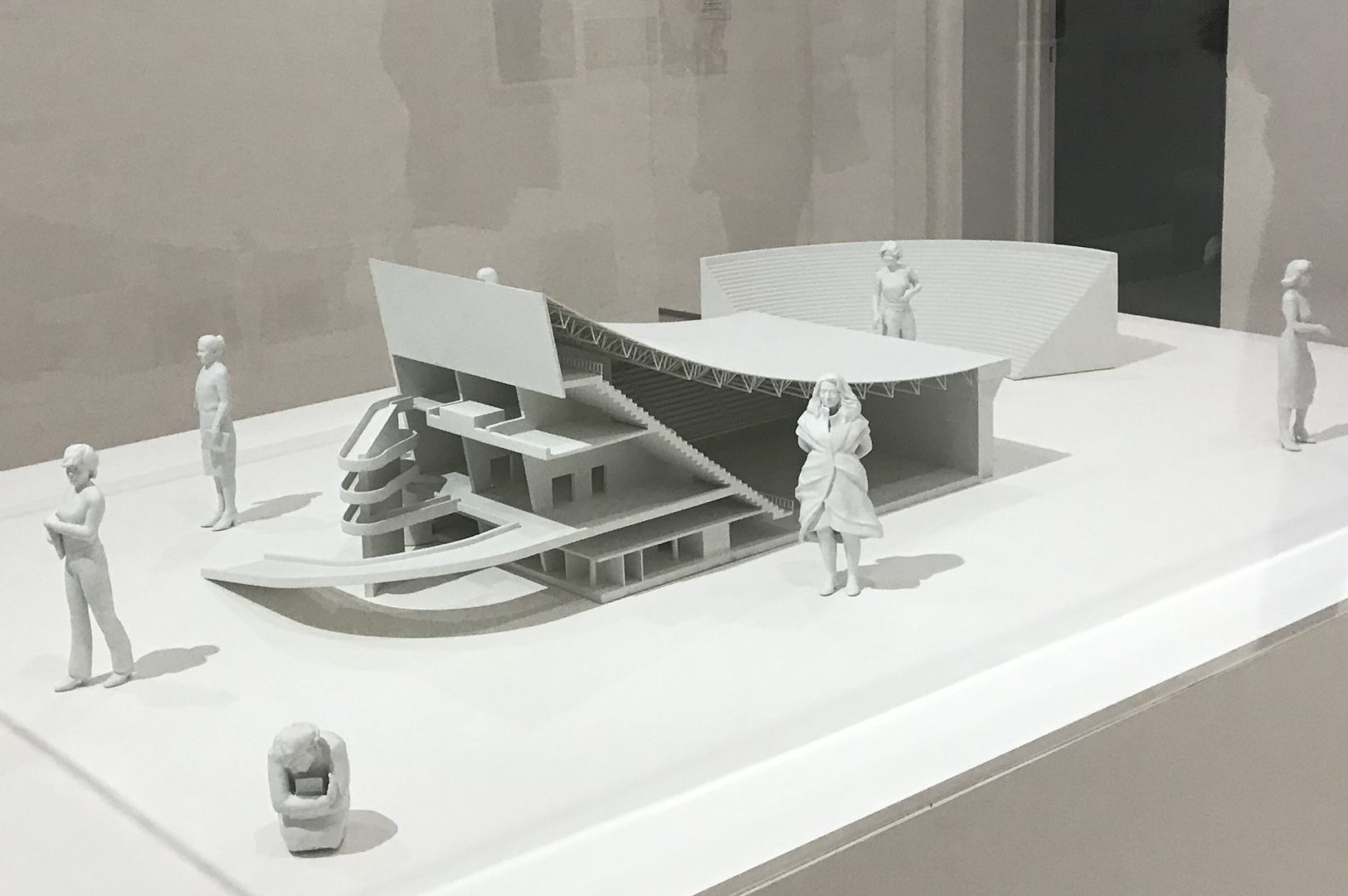

The conceptual work Plan (fem.) For Greater Baghdad by Jordanian artist Ala Younis creates an intersection between modern architecture, a gymnasium designed by Le Corbusier in the 1950s, and the influence of female artists, architects and others who have contributed to the development of a modern Baghdad. The Le Corbusier gymnasium was built after the architect died and in the 1980s under the patronage of Saddam Hussein for which it was named. It was occupied by U.S. troops in 2003 and has been deteriorating for many years. Younis uses this building as an anchor from the recent past to link with influential women such as world-renown architect Zaha Hadid, Balkis Sharara, the wife of architect Rifat Chadirji and who carried on with her husband’s practice while he was incarcerated, as well as artist and author Nuha al-Radi (Iraqi), whose work also appears in this show. Al-Radi’s stick figures made with narrow pieces of wood, metal and paint are arranged into small groupings that recall the artist’s family and friends in a similar twist to Hiwa B’s bell that transforms founds objects from acts of destruction into forms that are soothing to artist and viewer.

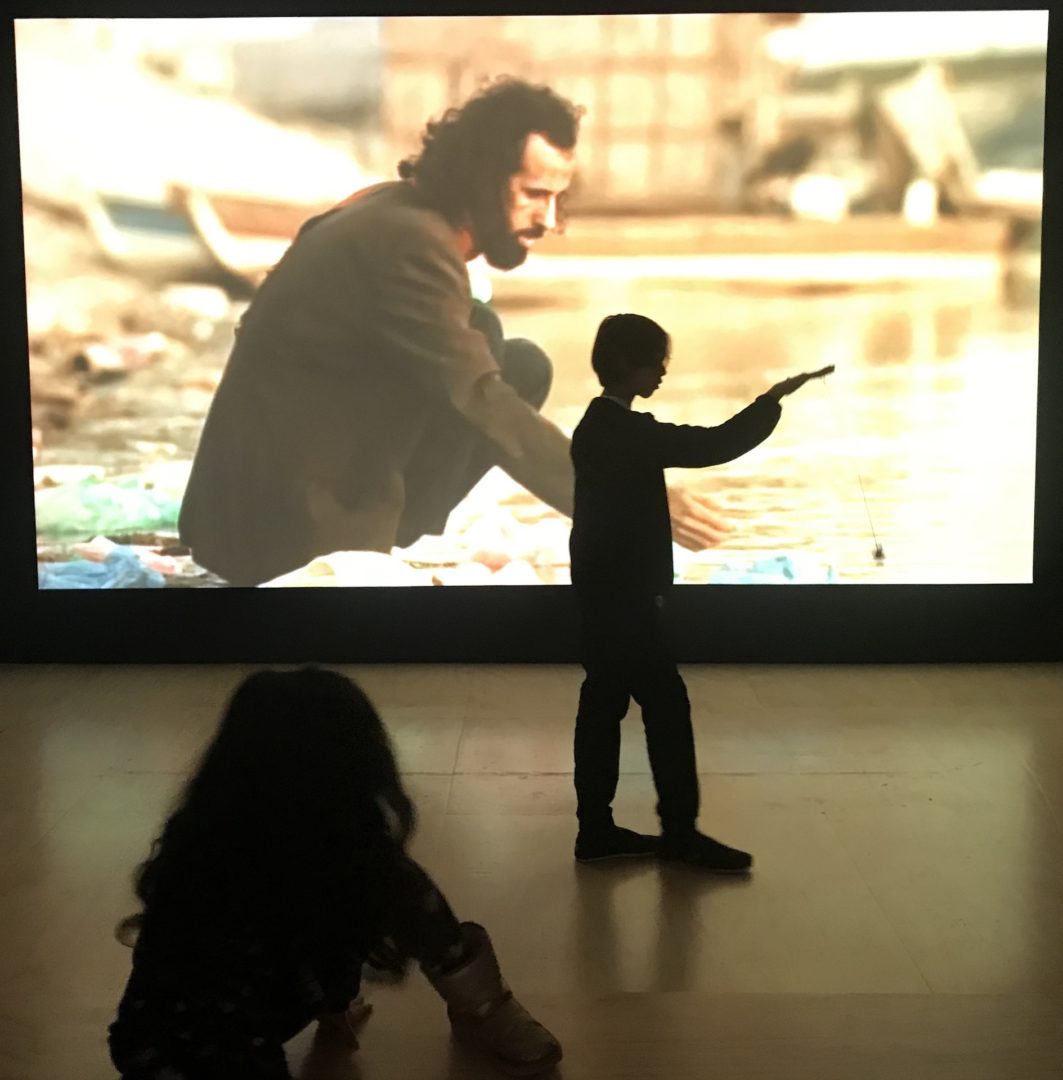

Filmmaker Ali Yass (Iraqi), did not contribute a film but instead recreated childhood drawings that his family was forced to leave behind when they fled from Iraq after the 2003 invasion. This piece hit home for me because we have a hallway in my home devoted to the artwork of my two children from the time they each started pre-school through the present. This hallway wallpapered with my children’s art is probably my most-treasured aspect of our home, a revelation I had while looking at Yass’s drawings and its reference to countless lost childhoods. On the closing day of this exhibition and in conjunction with the #momadivest protests, Yass wanted protesters to destroy these works on paper in the gallery but in anticipation of this action, museum officials removed these works from the walls. Protester were left to rip copies of these works while standing in the museum gallery.

This exhibition was spread throughout the entire museum taking over all of the galleries and providing ample space for numerous voices and critiques from the East and West, or both, that patiently worked through a complicated history. One of the small rooms off the main galleries was taken over by the video Evil.16: (Torture.Musik) by American artist Tony Cokes. The artist flashed excerpts of text from an article by Moustafa Bayoumi, originally published in The Nation magazine on December 26, 2005, that lays out in detail how music was used to torture detainees in Abu Ghraib, Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay. The big, bold text that was contrasted with bright, solid-colored backgrounds was projected against the back wall of the room and accompanied by samples of the many songs referenced in this article blasted from speakers at uncomfortably high volumes. This room’s overstimulation of the senses simulates the torture methods described in the text. Cokes’s installation both attracted and repelled me, which I imagine was intentional. This piece brought to mind the graphic and notorious photographs of U.S. troops abusing Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib, images that have become synonymous with the early years of the U.S. occupation. Without the use of graphic imagery or explicit text, Cokes manages to not only bring Bayoumi’s article to life but in such a way that it is just as horrifying as the actual photographs from Abu Ghraib.

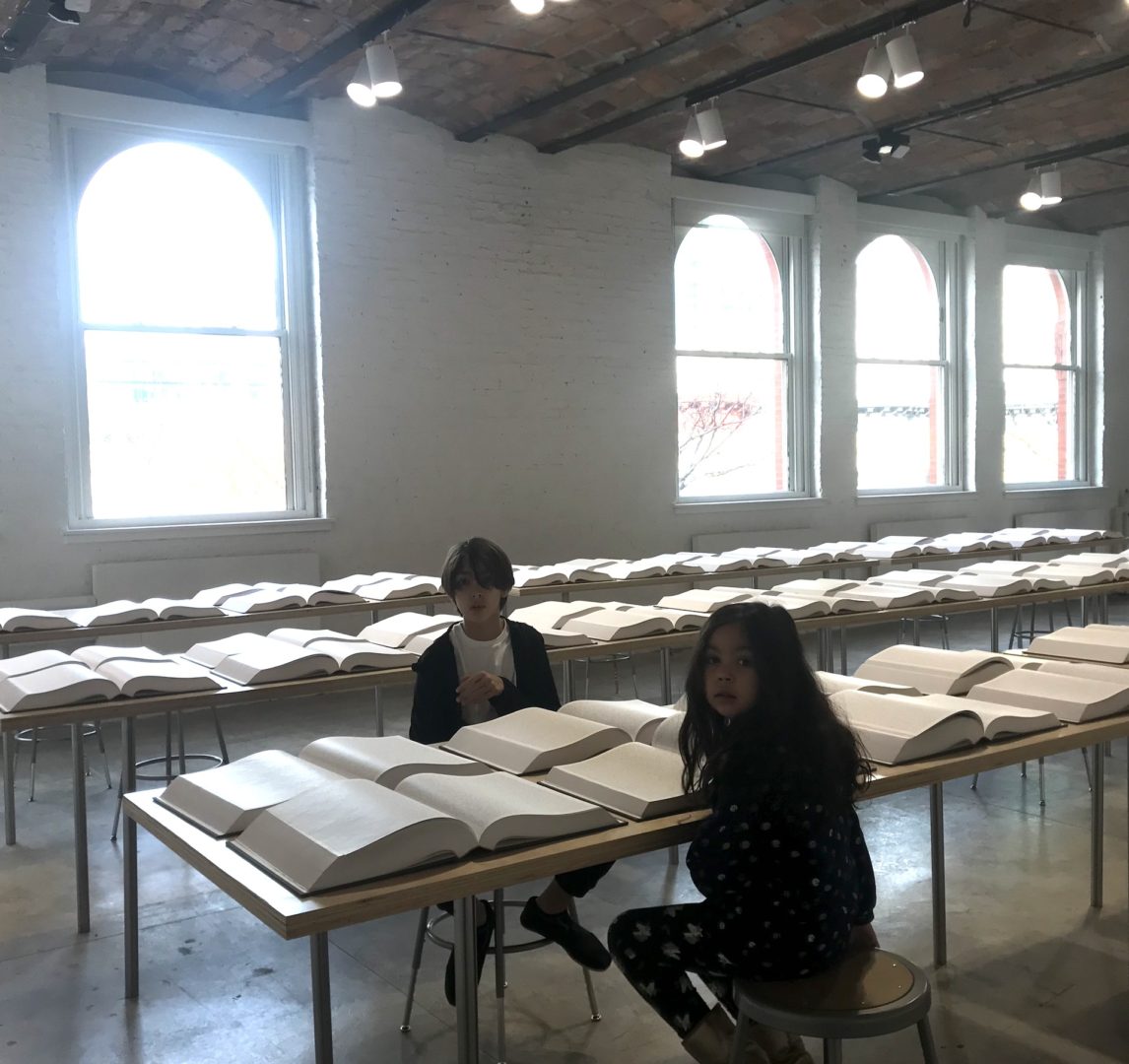

As a westerner, when I think of Iraq, I am overwhelmed by its complicated history of just the past thirty years and going into this exhibition, I wondered if I was prepared. These wars have generated massive amounts of media coverage, news articles and literature that I have a passing knowledge and awareness of in respect to the massive amounts of information we are exposed to on a daily basis. Australian artist Rachel Khedoori’s installation of large volumes of text spread across tables that fill an entire gallery presents all news articles containing the words “Iraq,” “Iraqi,” and “Baghdad” from 2003-2009. Visitors were invited to sit on stools and look through these volumes of texts, which my kids did so with delight to have found an interactive work that they could touch. As they looked through the enormous volumes filled with pages of small print text, they informed me that it would take them a lifetime to read all of these articles. Their bewilderment was not an overstatement and in many ways articulated how I have felt it my own efforts to keep abreast of the situation in Iraq.

I can say with certainty that this exhibition was one of the best shows that I have seen recently. I thoroughly appreciated the curatorial choices and was thrilled to be introduced to a number of artists whose work I will continue to seek out.

For more about family travel click here.

Click here if you are looking for a little guidance planning your next vacation.