Day tripping around the city and taking full advantage of the parks and beaches, while observing social distancing guidelines, just about sums up our summer 2020 plans. Aside from outdoor art installations, opportunities to see and experience art and culture remain virtual. Art galleries around New York City are cautiously re-opening but it is unclear when the public will be permitted to visit museums again. In the meantime, many cultural institutions, art spaces and individuals have continued to offer online cultural experiences to fill this void.

The powerful resurgence of the Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality has expanded into a much broader movement exposing the full scale of injustices that permeate our institutions. This moment is defined by calling out, cancelling and searching for new paths forward and the critique of art institutions is the exhibition that is happening right now. It is all over the internet and circulating across social media outlets. A chorus of diverse voices from within as well as those outside the art institution is driving this communal effort to undermine ignorant practices. These critiques encompass the curatorial, collecting and administrative practices of museum staff and board members. This critique has also re-opened debates over racist monuments that memorialize white supremacist histories. Some monuments have been toppled while others are being removed with the consent of descendants. Art and activism have reunited, history is in the making and we bear witness to these progressive actions while scrolling through our phones.

These institutional critiques inspired me to dig through my own memories and re-visit exhibitions that impacted me in the past but have resurfaced in light of current events. This train of thought inspired me to write about the Queens Museum of Art. For decades, this quiet yet wildly refreshing and perhaps under-recognized institution has been consistently mounting exhibitions representing a broad range of artists as well as connecting with the diverse neighborhoods of Queens. This museum is located in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park (the Central Park of Queens) and is surrounded by a beautiful patchwork of immigrant communities from all over the world. On any given day, the park grounds are filled with family picnics, birthday parties, soccer games, and food vendors using a variety of inventive and makeshift carts to sell specialties from their countries of origin. There is a liveliness and community spirit flowing through this park that is definitively and unmistakably Queens.

I looked through the Queens Museum of Art’s exhibition history and was awestruck by the countless exhibitions that have thoughtfully represented the art of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), past and present. Sadly, I have missed out on too many of these exhibitions for no good reason other than in NYC, we have so much to choose from and only so much time to see and do everything. Whether one is juggling school, work, and/or family, it is impossible to see it all.

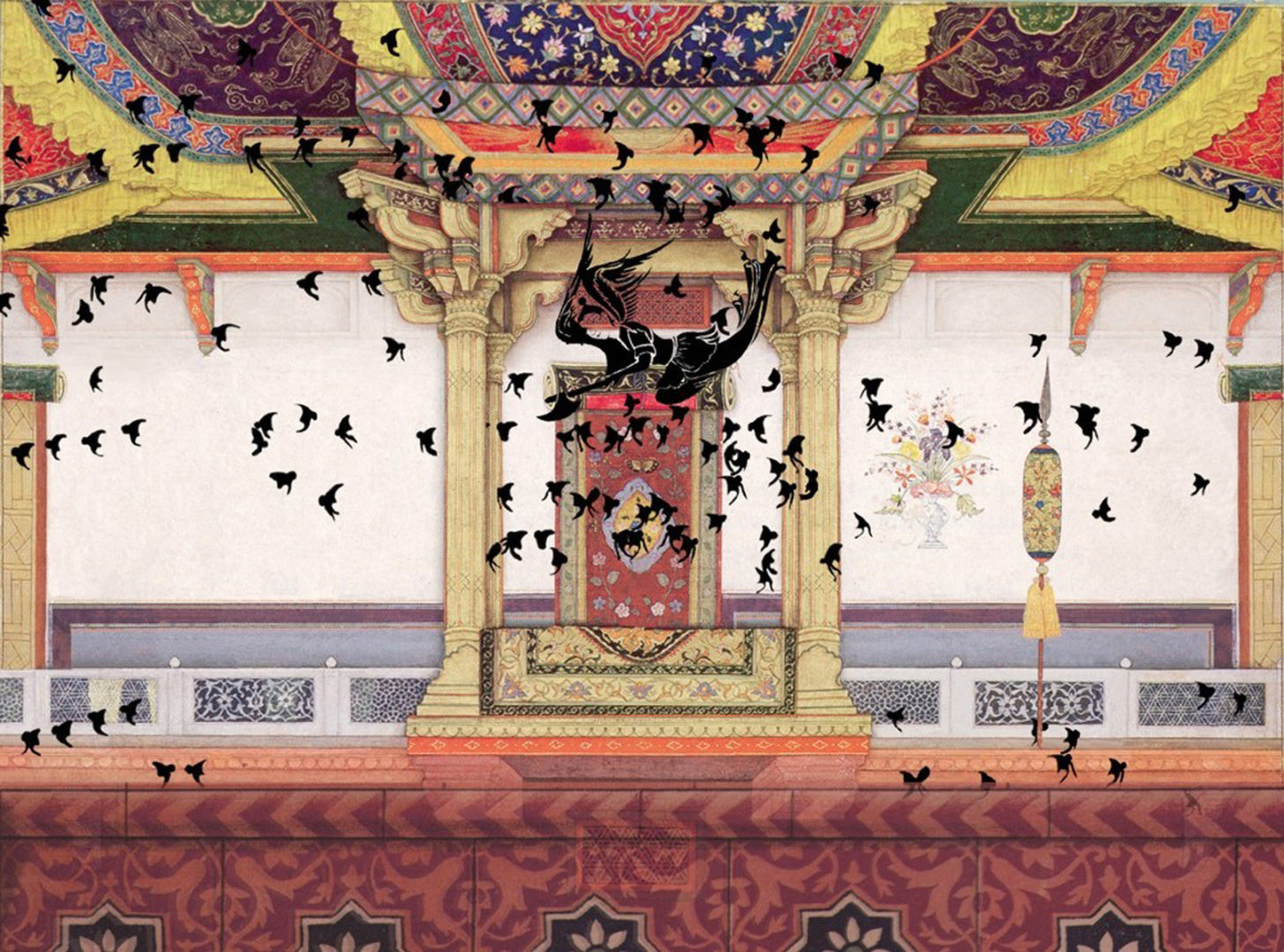

My own journey as a New Yorker has been marked by years of study, raising a family, running a business and my most recent return to writing after a long hiatus. When I was a graduate student living in Brooklyn, I visited the Queens Museum of Art for the first time to review an exhibition for an online art magazine. I attended a preview of Edge of Desire: Recent Art in India, an exhibition that was spread between this museum and the Asia Society and Museum in Manhattan. To compliment this exhibition, the Queens Museum of Art also mounted Fatal Love: South Asian American Art Now. These shows were up from February 27 to June 5, 2005, and my review of Edge of Desire has been re-posted here to give one a better sense of my response to this exhibition fifteen years ago. As these exhibition titles indicate, these institutions have used their platforms as spaces for intellectual dialogues to develop around artists of the South Asian Diaspora. Since my early years as a student of Art History and as a woman of color, my interests have consistently gravitated towards the art of BIPOC. I am therefore grateful to the Queens Museum of Art for churning out a steady stream of exhibitions that have presented diverse interpretation of modern and contemporary art.

As a frequent visitor, I cannot speak to the nature of this museum’s work environment and do not presume to assert a utopian scenario. However, I am enchanted by its historical connection to the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs, its public programming and community outreach. The museum’s building was originally constructed for the 1939 World’s Fair, was the temporary headquarters for the United Nations General Assembly (1946-1950) and exhibited the Panorama of New York City for the 1964 World’s Fair. The Panorama has been updated and is a on permanent view in this building that became the Queens Museum of Art in 1972. World’s Fair relics are displayed in cases but the grandest symbol stands right in front of the museum – the Unisphere from the 1964 fair. These World’s Fairs attracted visitors from all over including my parents, my father from Bangladesh and my mother from Puerto Rico, who were just married in 1964 and had just embarked on their new life in this country on the Lower East Side in Manhattan.

The Queens Museum of Art is a place where someone like myself can find traces of one’s personal narrative among the among the many narratives presented by this museum. In addition to the examples above, a couple years ago I attended the Ecuadorian Film Festival with our two kids and my husband, an immigrant from Ecuador. This cultural institution does not generalize the histories and cultures of BIPOC but instead allows time and space for individual for specifics narratives to surface.

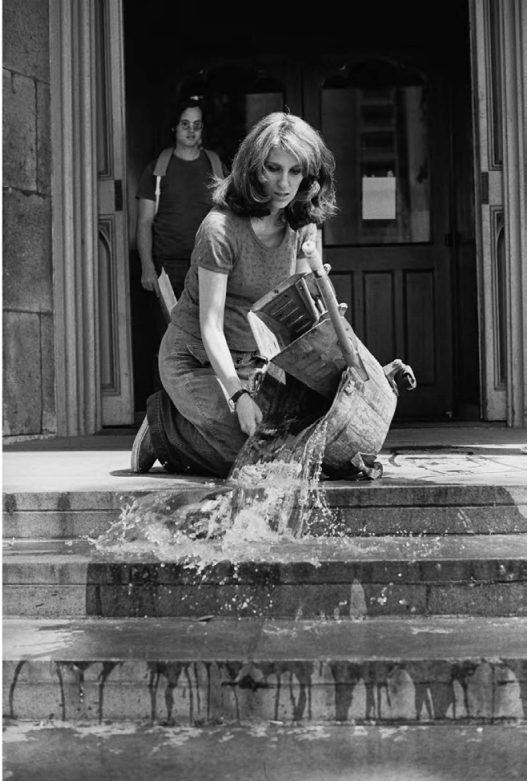

Another memorable moment at the Queens Museum of Art was the survey exhibition Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art (September 18, 2016 to February 19, 2017). This was one of the first times since having kids that I went to a museum by myself, a personal milestone. Also, it had been almost a decade since I had left graduate school and essentially stopped writing (or thinking) about art because I was seriously burnt out. Looking at Ukeles’s earlier works from the 1970s brought me back to my years of studying feminist art. During that period of my life and before I had children, I used my mother’s own experiences as a reference point for relating to feminist critiques deconstructing conventional notions of motherhood. When I walked through the Ukeles exhibition at the Queens Museum of Art, I had the opportunity to contemplate and re-process this work through the prism of my own experiences as a mother.

The artist’s Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! “CARE,” A Proposal for an Exhibition differentiates development and maintenance as it applied to her own development and maintenance as a woman, artist, mother and wife (in no particular order). She put forth the idea that they do not need to be separate but can be interchangeable and that her domestic duties, if moved into the public sphere and within an institutional context, could be identified as art. It was not until July of 1973 that she had the opportunity to realize a series of Maintenance Art Performances at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford Connecticut. The artist assumed the daily tasks of the museum’s maintenance staff during operating hours and defined these act as works of art.

On July 20, 1973, she was given the keys to all of the doors throughout the museum, including the staff offices, and Ukeles took this opportunity to close off sections of the galleries and offices during operating hours (The Keeping of the Keys: Maintenance as Security). On this day, she performed another task of a museum maintenance worker by dusting the case of an Egyptian mummy on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Transfer: The Maintenance of the Art Object). After cleaning the case and marking it as a work of art, she demonstrated with a handwritten chart how this designation of the display case as an art object transferred the responsibility of its care from the maintenance worker to the museum conservator. On another day of performances, Ukeles washed the floors inside and outside the museum as she would at home (Washing, Tracks, Maintenance: Inside and Washing, Tracks, Maintenance: Outside, July 22, 1973). Looking at the photographs and documentation from these performances reminded me of interests that I had forgotten about after my abrupt departure from graduate school. It was on this day in 2017 at the Queens Museum of Art that I realized it was time to start a new chapter in my own development as woman, wife, mother, thinker (in no particular order).

“The sour ball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?” [Excerpt from Ukeles Manifesto, 1969]

Ukeles’s performances, were not only a transfer of domestic duties to the public sphere but also recognition of the under-recognized staff members of the museum world – the maintenance workers. Under normal circumstances, the people in these positions are not properly compensated, under-appreciated and rarely acknowledged by upper-level staff and visitors to the museum. These performances made visible the invisible – unpaid domestic labor and low-paying maintenance work – through an inversion. In 1977, Ukeles was invited by the NYC Department of Sanitation to be an artist-in-residence, a position that she holds to this day. In this role, she has developed an art career examining this city’s dependance on the sanitation department and its staff of essential workers.

Our current attention to essential workers during these unprecedented times reminded me of Ukeles’s career. While we were ordered to stay home, essential workers reported to work to attend to the sick, collect the garbage, stock the shelves of grocery stores, deliver take-out and groceries, maintain our public transit system for these essential workers and so much more. Scrolling through my Instagram feed, I came across numerous live videos from museums showing their security and maintenance staff members walking through empty galleries. These museum workers were unexpectedly thrust into the spotlight as institutions quickly switched gears and started to generate a new type of content for viewers stuck at home. Meanwhile essential workers continue to experience poor working conditions, inadequate pay and limited access to personal protective equipment.

In closing, the Queen Museum of Art was featured in Stella Meghie’s film The Photograph (2020). Watching this film during the stay-at-home order was a comforting reminder of this museum’s role in our city. The female lead played by Issa Rae, of HBO’s Insecure, is a curator at the Queens Museum of Art. The film concludes with a survey exhibition organized by Rae’s character of her late-mother’s body of work. The mother was a renown photographer who rose to prominence in the 1980s in New York City. Although fictional, the choice of the Queens Museum of Art as the setting for a Black, female curator to oversee a survey of a Black, female photographer did not require a stretch of the imagination. I applaud the filmmaker for this decision but also applaud the Queens Museum of Art for its track record.

For more posts about art around New York City and abroad click here.

For more about family travel, local (NYC) and abroad, click here.

Click here if you are looking for a little guidance planning your next vacation.